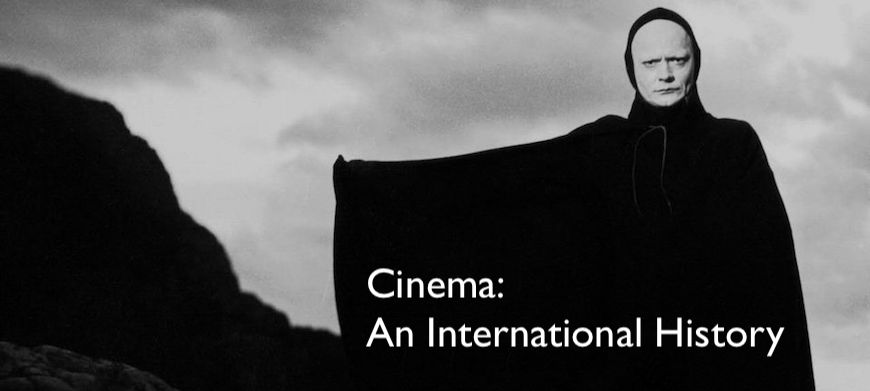

The Invention of CinemaThe history of film began in the late nineteenth century, with the invention of ‘magic lantern’ optical toys (such as the Phenakistoscope and the Zoetrope), which presented short, repetitive animations exploiting the eye’s persistence of vision. Coleman Sellers modified the Zoetrope, replacing its hand-drawn images with photographs, creating the Kinematoscope in 1861. Henry Renno Heyl then projected a series of Kinematoscope photographs, using his Phasmatrope device, in 1870. Émil Reynaud invented a Zoetrope-like device called the Praxinoscope, which functioned as both a camera and a projector. Although Reynaud’s images were all hand-drawn rather than photographic, they were presented on strips of celluloid (rather than on the discs used by all previous devices). Reynaud used his Théâtre Optique machine to project Pantomimes Lumineuses presentations. His first public screening was a projection of Pauvre Pierrot (‘poor Pierrot’, 1892). Similarly, in 1886, William Friese-Greene collaborated with John Arthur Roebuck Rudge on a Biophantascope capable of projecting magic lantern slides in rapid succession. Eadweard Muybridge used a Zoopraxiscope — a series of cameras, operated in rapid succession — to photograph the movements of a horse’s legs. His results, published in 1878, seem in retrospect to be prototypical (albeit horizontal) film strips. Étienne-Jules Marey enhanced Muybridge’s technique, creating a single camera capable of capturing a series of rapid exposures which he called Chronophotographie. Otto Anschutz invented a device capable of projecting Chronophotographie images in rapid sequence, and he first demonstrated this Electrotachyscope in Berlin in 1894.  1880sFilm of the decade: The very first moving photographic images were filmed in 1888. Louis Le Prince, using a camera he had invented himself, recorded approximately two seconds of ‘actuality’ footage known as Roundhay Garden Scene in Leeds, England. Le Prince also projected his footage, from a paper filmstrip, using projectors he designed himself. Le Prince built his first projector in Paris in 1887, and produced two further models in Leeds later that year. Projection speeds for silent films were not standardised. Each of Le Prince’s devices projected at a different rate: twelve, sixteen, and twenty frames-per-second. As early cameras and projectors were hand-cranked, frame-rate consistency was not always maintained, though sixteen frames-per-second was the average speed in the silent era. Subsequently, twenty-four frames-per-second became the industry standard for sound films.  1890sFilms of the decade: Thomas Edison, inventor of the cylinder phonograph, also experimented with cylindrical film recordings, using a Kinetoscope camera developed with his assistant, W.K.L. Dickson. In 1893, after modifications, the Kinetoscope was consolidated as a hand-cranked machine displaying celluloid filmstrips to individual viewers, known as a Kinetograph. The first film shown to the public in this manner was Blacksmith Scene (1893). A year later, Charles Francis Jenkins invented the Phantoscope projector in Indiana, and refined it with Thomas Armat. Their Phantoscope patent was then sold to Edison, who renamed it the Vitascope and used it to project Kinetograph films in 1896. In early 1895, the brothers Gray and Otway Latham developed and publicly demonstrated a film projection system in New York. The Lathams were assisted by W.K.L. Dickson, who had previously worked with Edison, and their device was known as a Panopticon. In Berlin, the brothers Max and Emil Skladowsky designed a Bioskop camera which recorded and projected two simultaneous images, each at eight frames-per-second, creating the illusion of sixteen frames-per-second projection. Their Bioskop was demonstrated to the public in late 1895. Despite numerous antecedents (such as Louis Le Prince, Charles Francis Jenkins, the Lathams, and the Skladowskys), the brothers Louis and Auguste Lumière are generally credited as the pioneers of projected film. The Lumières utilised a Cinématographe camera/projector, patented by Léon Bouly in 1893 (originally called a Cynématograph, in 1892), to project moving images onto a large cinema screen. The first film the Lumières projected was La Sortie de l’usine Lumière à Lyon (‘workers leaving the Lumière factory in Lyon’), in Paris at the very end of 1895. The film shows workers leaving the Lumière’s factory gate at the end of a shift. This was typical of the Lumière’s early films, which were all brief documentaries detailing events from everyday life. One exception was their short comedy Le Jardinier et le petit espiègle, also from 1895 (advertised as Pranks on a Gardener when it was shown in the UK in 1896), technically the first film with a fictional narrative. Their primary significance was not in their content but rather in the medium itself. Like still photography, x-rays, air travel, and high-speed land travel, all popularised at the turn of the twentieth century, the cinema offered a new perspective from which to view the world. The early films of the Lumières and others are now regarded as a ‘cinema of attractions’, offering novelty and spectacle rather than narrative. (Many of these early shorts were also frequently remade and retitled.) When the Lumières’ films were screened in Japan, they were accompanied by live narration performed by benshi, and each sequence was projected on a continuous loop (a technique known as tasuke). The benshi originally introduced each film by providing an explanation of its exposition, though later their performances became more sophisticated. Actors would stand behind the screen, interpreting the film as a live drama, known as kagezerifu.  1900sFilms of the decade: Cinema’s exponential technological advancement was demonstrated in 1900 by Raoul Gromoin-Sanson, who unveiled his Cinéorama system. Cinéorama featured an enormous panoramic screen, onto which were projected ten simultaneous images side by side. The result was certainly spectacular, though the flammability of nitrate film reels, coupled with the logistics of synchronising ten projectors, curtailed the system’s commercial potential. It would later influence Abel Gance’s Napoléon and Hollywood’s Cinerama process. Primitive cinema initially consisted of simple Lumière ‘actualities’, though French stage magician Georges Méliès sought to fully explore the camera’s potential for illusion. He used editing and trick photography to create films in which objects and people appear, disappear, multiply, explode, grow, and shrink. These stop-motion effects influenced early cartoon animators such as James Stuart Blackton (Humorous Phases of Funny Faces, 1906) and Émile Cohl, director of Fantasmagorie (‘phantasmagoria’, 1907). Méliès’ film screenings were accompanied by narration provided by bonimenteurs, similar to Japanese benshi. Méliès’ masterpiece was a science-fiction tale about a group of curious Victorians exploring the lunar surface, A Trip to the Moon (Le voyage dans la lune, 1902). It was more than ten times longer than any previous film, a remarkable attempt at a sustained narrative which predates Edwin S. Porter’s early western The Great Train Robbery (1903). The first truly feature-length film was Charles Tait’s The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906), made in Australia.  1910sFilms of the decade: D.W. Griffith’s early short films (such as the gangster film The Musketeers of Pig Alley, 1912) were the first to combine all the new narrative devices, including cross-cutting, multiple camera positions, intertitles, and close-ups. Griffith can thus be seen as the first modern director, and his greatest achievements were the historical epics The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Intolerance (1916; subtitled A Sun-Play of the Ages: A Drama of Comparisons and Love’s Struggle Throughout the Ages). The Birth of a Nation attracted protests and criticism for its heroic portrayal of the Ku Klux Klan, and its technical accomplishments are tarnished by its overt racism. It was, however, the Italian studios that produced the very first epic films, including Quo Vadis? (Enrico Guazzoni, 1913) and Giovanni Pastrone’s stunning Cabiria (Visione storica del terzo secolo A.C., 1914). In contrast to these historical epics was Arnaldo Ginna’s film Vita futurista (‘Futurist life’, 1916), directed according to the Futurist cinema manifesto by F.T. Marinetti, which envisioned Futurist cinema as an amalgamation of other forms of visual art: “Painting + sculpture + plastic dynamism + words-in-freedom + composed noises + architecture + synthetic theatre = Futurist cinema” (1916). Screen comedian Charlie Chaplin emigrated from London to Hollywood. There, he directed and starred in a series of single-reel silent comedies, including The Tramp (1915), which made him the most recognisable film star in the world. Together with D.W. Griffith, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks, Chaplin founded the independent studio United Artists in 1919. Fairbanks specialised in swashbuckling roles such as The Mark of Zorro (Fred Niblo, 1920), which anticipated those of Errol Flynn in the 1930s (The Adventures of Robin Hood; Michael Curtiz, 1938). United Artists was eventually sold in 1952, and later merged with MGM. The world-famous stage actress Sarah Bernhardt starred in Louis Mercanton’s Elizabethan costume drama Les amours de la reine Élisabeth (‘the loves of Queen Elizabeth’, 1912), one of France’s film d’art (art film) productions. The first example was L’Assassinat du duc de Guise (‘the assassination of the Duke of Guise’, 1908), directed by Andre Calmettes and Charles Le Bargy. Films d’art were significant for their extended running-times, though their static camerawork and stage-like sets were more regressive than innovative. A similar trend existed in Germany, with the popularity of Autorenfilme (literary adaptations), starting with Max Mack’s Der Andere (‘the other man’, 1912). The Autorenfilme became increasingly elaborate, leading to opulent costume dramas known as Kostumefilme, a trend begun by Joe May’s Veritas Vincit (1918) though dominated by Ernst Lubitsch (notably his Mme du Barry, 1919). The brief period between 1908 and 1911 was seen as a bela epoca (golden age) for Brazilian cinema, among the most popular productions being fitas cantatas films accompanied by live singers. Similar to Brazil’s fitas cantatas were the Japanese rensa-geki films, in which each sequence would be followed by a short dramatic scene (an innovation first introduced in 1916). Other Japanese genres of the period were: nonsensu-mono (comedies), matatabi-mono (films about wandering outlaws, such as Hiroshi Inagaki’s 天下太平記 (‘peace on Earth’, 1928), bunka eiga (documentaries, later called kiroku eiga), and jiji eiga (also documentaries, though specifically jingoistic).  1920sFilms of the decade: Erich von Stroheim, who emigrated from Austria to America, directed the epic Greed (1924), though it was cut by the studio from seven hours to two hours. French director Abel Gance’s films — notably La roue (‘the wheel’, 1923) and the stunning ‘biopic’ Napoléon from 1927 — were similarly extravagant. Napoléon had a running-time of over five hours, and was projected using the Polyvision system: three screens were used, enabling incredible panoramic images to be presented. Polyvision was influenced by the ten-projector panoramas of the French Cinéorama system of 1900, and it inspired the American Cinerama process of the 1950s. Similar effects were later achieved using split-screen techniques, as in Richard L. Bare’s Wicked, Wicked (1973; filmed in Duo-Vision). The Hollywood Studio SystemCharlie Chaplin’s silent comedy shorts of the 1910s developed into feature-films in the 1920s and 1930s, notably The Gold Rush (1925) and City Lights (1931). (Chaplin resisted the industry’s transition to sound and dialogue, though he did use sound effects and synchronised scores.) Buster Keaton’s The General (1927, directed by Keaton and Clyde Bruckman) is another enduring silent comedy. Other Hollywood stars of the era included sex-symbol Rudolph Valentino, whose most popular leading role was in the exotic drama The Sheik (George Melford, 1921). In contrast to the decadence of Hollywood’s emerging star and studio systems was Robert Flaherty’s humanist documentary Nanook of the North (1922), praised by John Grierson who wrote one of the first analyses of documentary films (First Principles of Documentary, 1932). Grierson has been credited with coining the term ‘documentary’, though he disputes this: “Documentary is a clumsy description, but let it stand. The French who first used the term only meant travelogue.” American film production in the early 1920s was increasingly consolidated around a small number of film studios, all based in Hollywood, which became synonymous with the American film industry. This system of classical Hollywood studio production survived until the 1960s, when it would be challenged by the increasing popularity of television and the rise of independent film production. Hollywood’s first blockbuster of the post-silent era was the ‘talkie’ The Jazz Singer (Alan Crosland, 1927), as its sporadic lines of spoken dialogue caused an instant sensation. Oskar Messter had produced Tonbilders (films with synchronised sound) in the 1900s, and, while The Jazz Singer may have been technically inferior to these earlier experimental sound films, its commercial success led directly to the demise of silent cinema. Silent Cinema in JapanWith the introduction of sustained narratives to Japanese cinema, the country’s film industry began to polarise into two distinct styles: gendai-geki (dramas with contemporary settings, initially influenced by German Expressionism) and jidai-geki (period dramas influenced by kyu-geki historical films). Kichizo Chiba’s 己が罪 (‘my sin’, 1909) was one of the earliest examples of gendai-geki. One of the earliest jidai-geki films was 忠臣蔵 (‘the loyal retainers’, 1907), by Ryo Konishi. Another, Bansho Kanamori’s 紫头巾浮世绘师 (‘purple headscarf’, 1923), is also an early example of the ken-geki genre (samurai sword-fighting films, also known as chambara). Daisuke Ito’s A Diary of Chuji’s Travels (忠次旅日記, 1927) represents the pinnacle of early jidai-geki cinema and is also a yakuza-geki prototype. Yakuza films were initially chivalrous and known as ninkyo-eiga, a trend initiated in 1964 by Shingehiro Ozawa’s 博徒 (‘puzzle’); in the 1970s, they became more realistic, a jitsuroku-eiga style popularised by Kinji Fukasaku’s Battles Without Honour and Humanity (仁義なき戦い) in 1973. Shomin-geki films (comedies of social observation about lower-middle-class life) include Yasujiro Shimazu’s Father (お父さん, 1923). The shomin-geki social comedies led to a series of satirical comedies known as modan-mono, such as Yutaka Abe’s 足にさわった女 (‘the woman who touched her legs’, 1926). A group of overtly Marxist films, known as keiko-eiga, were swiftly suppressed by the Japanese authorities. Amongst them was Kenji Mizoguchi’s Tokyo March (東京行進曲, 1929). One of the final keiko-eiga films was Shigekichi Suzuki’s What Made Her Do It? (何が彼女をそうさせたか, 1930), the highest-grossing film in Japanese silent cinema. Weimar ExpressionismGerman Expressionism, the cinema’s first avant-garde movement, emphasised atmosphere at the expense of realism. Angular, distorted designs, including artificial lighting and shadows, were painted directly onto the set walls. Actors were encouraged to create wildly stylised performances. Unconventional camera angles were employed. Elements of the Expressionist style would later appear in the films of Orson Welles, in Universal’s 1930s horror films, and in film noir. Fritz Lang’s superproduction Metropolis (1927) almost bankrupted Germany’s premier studio, UFA. Lang also made the chilling M (1931), and later produced a series of Hollywood thrillers including The Big Heat (1953). F.W. Murnau directed Nosferatu (Eine Symphonie des Grauens, 1921) and the naturalistic Kammerspielfilm The Last Laugh (Der Letzte Mann, 1924) in Germany, and Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927) in America, only to be killed in a road accident a few years later. A series of films influenced by the New Objectivity movement, beginning with Karl Grune’s The Street (Die Straße, 1923) and G.W. Pabst’s Joyless Street (Die Freudlose Gasse, 1925), provided a contrast to the extreme stylisation of Expressionism. The films of this period were concerned with poverty-stricken life on the streets, hence they are known as Straßenfilme (street films). Simultaneously, D.W. Griffith also made a street film, Isn’t Life Wonderful? (1924), filmed on location in Germany.  Avant-Garde CinemaThe cinematic avant-garde can be traced back to two European silent films: Abel Gance’s experimental La folie du docteur Tube (‘the madness of Dr Tube’, 1915) and Robert Weine’s Expressionist masterpiece The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (Das Cabinet Des Dr. Caligari, 1919). The intersection of art and cinema in the 1920s led to a flowering of the cinematic avant-garde; Iakov Protazanov’s Aelita (Аэли́та, 1924), for example, is the only known film from the Constructivist art movement, and Alexei Gan’s Constructivist manifesto celebrated “the vitality of the cine platform of constructivism” (1928). American avant-garde cinema, however, has much later origins: Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid’s Meshes of the Afternoon from 1943, and Kenneth Anger’s Fireworks from 1947. Caligari was a film d’art production in all but name, with its painted scenery and static camera, though its angular sets were designed with complete disregard for realism. This resulted in a film that stylistically echoed the unbalanced psychology of its sinister central character and his somnambulistic assistant. Caligari was also a direct influence on James Whale’s Frankenstein. In France, Danish director Carl Theodore Dreyer made The Passion of Joan of Arc (La passion de Jeanne d’Arc, 1928) and Spaniard Luis Buñuel (with assistance from artist Salvador Dalí) gained entry into the Paris Surrealists’ group with Un chien andalou (‘an Andalusian dog’, 1928). The latter film, an iconoclastic masterpiece of enigmatic, shocking, and deliberately provocative dream imagery, features a woman’s eye being sliced open with a razor, ants crawling from a hole in a man’s hand, and dead donkeys lying on pianos. Buñuel subsequently worked extensively in Mexico, where he directed The Young and the Damned (Los olvidados, 1950) and the surreal The Exterminating Angel (El ángel exterminador, 1962). He returned to France in the 1960s and made the sexual fantasy Belle de jour (‘lady of the daytime’, 1967). Absolute films, influenced by the Dada art movement, included Hans Richter’s Rhythmus ’21 (‘rhythm 21’, 1921), Viking Eggeling’s Diagonal Symphony (Diagonalsymphonien, 1921), Entr’acte (Rene Clair, 1924), and Walther Ruttmann’s Lichtspiel Opus I (‘light show I’, 1921), which was the first abstract film screened to the public. Dada was represented on film by Marcel Duchamp’s Anaemic Cinema (1925) and Man Ray’s La retour à la raison (‘the return to reason’, 1923). Many of these semi-abstract art films are examples of cinematic Impressionism, juxtaposing images to give them new meanings, as the montage theorists in Russia would later advocate. Fernand Léger’s Ballet mécanique (‘mechanical ballet’, 1924) was another experimental semi-abstract film, influenced by Russian montage editing. Total abstraction was achieved by Henri Chomette, the French director whose works of ‘pure cinema’ included Five Minutes of Pure Cinema (Cinq minutes de cinema-pur, 1925), depicting abstract patterns of light. Soviet MontageImpressionism in film was made possible by the work of Lev Kuleshov, the Russian director who investigated the psychological impact of montage. Kuleshov intercut a picture of Ivan Mozhukhin’s expressionless face with images of a bowl of soup, a dead body in a coffin, and a little girl. After the shot of the soup, audiences perceived the face as appearing hungry; it was interpreted as mournful after the shot of the coffin; finally, it was viewed as happy after the little girl. Thus, Kuleshov discovered that juxtaposition could alter the meaning of images. Following in the tradition of the agit-trains that projected political propaganda to Russian peasants, theorist Sergei Eisenstein harnessed the political potential of Kuleshov’s montage. In 1929, he identified five types of montage: metric, rhythmic, tonal, overtonal, and intellectual. He was then commissioned by the Russian government to produce cinematic commemorations of the Russian Revolution, including Battleship Potemkin (Бронено́сец «Потёмкин», 1925) and October: Ten Days that Shook the World (Октябрь: Десять дней, которые потрясли мир; 1928). Potemkin, which dramatised the 1905 naval revolt at Odessa, contains arguably the most celebrated sequence in silent cinema: the massacre on the Odessa Steps. Alongside Eisenstein’s films, the greatest Soviet films of the silent era were Vsevolod Pudovkin’s Mother (Мать, 1926) and Aleksandr Dovzhenko’s Earth (Земля, 1930). Russian director Alexander Sokurov produced Russian Ark (Русский ковчег, 2002), a digital film consisting of a single continuous shot, the antithesis of Eisenstein’s montage editing. Following the German invasion during World War II, Soviet cinema was again harnessed for propagandist purposes, with a series of short films known collectively as kinosborniki. The first of these anti-Nazi propaganda films, Боевой киносборник (‘combat film collection’), was directed by Sergei Gerasimov, I. Mutanov, and Y. Nekrasov in 1941. The Russian public, however, preferred escapism to propaganda, and the most commercially successful films of the period were glamorous kolkhoz musicals such as Grigori Aleksandrov’s Circus (Цирк, 1936). While Eisenstein used montage to simulate and heighten reality, Dziga Vertov’s kinoki philosophy saw montage as a tool for the manipulation of realism. Vertov published a manifesto in 1922 (“‘Cinematography’ must die so that the art of cinema may live”), though his outstanding contribution to cinema is Man with a Movie Camera (Человек с кино-аппаратом, 1929). The film is a ‘city symphony’ documentary about everyday life in Moscow, though it uses techniques such as split-screen, double-exposure, trick editing, stop-motion, and freeze-frames to constantly remind the audience of the camera’s presence. Walther Ruttmann had previously directed a city symphony about Berlin, Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (Die Sinfonie der Großstadt, 1927); the first city symphony was Alberto Cavalcanti’s study of Paris, Nothing but Time (Rien que les heures, 1926). (Cavalcanti’s film featured a collage of disembodied eyes, a motif repeated a year later in Metropolis.) The innovations of Soviet montage and the French avant-garde were part of a wide-ranging modernist movement throughout the arts. Marcel L’Herbier’s L’inhumaine (‘the inhuman woman’, 1923) was resolutely modernist in its set design, though its outstanding artistic radicalism (like that of the overtly Expressionistic Caligari) inevitably made it commercially unsuccessful.  1930sFilms of the decade: The most popular actress of the period was Swedish icon Greta Garbo, who had been a silent film star since the early 1920s, notably in Flesh and the Devil (Clarence Brown, 1926). She later appeared (and, famously, spoke) in Clarence Brown’s Anna Christie (1930) and Edmund Goulding’s creaky Grand Hotel (1932), though she withdrew from public life in 1941. Director Leni Riefenstahl starred in several of the popular German mountainside films (known as Bergfilme) made by Arnold Fanck, including The Holy Mountain (Der Heilige Berg, 1926), though she did not feature in Fanck’s first example of the genre, Das Wunder des Schneeschuhs (‘marvels of the snowshoe’, 1921). Alongside the Bergfilme during the 1920s was a series of educational documentaries, made primarily by UFA, known as Kulturfilme; Riefenstahl appeared in the first significant example of these, Wege zu Kraft und Schönheit (‘paths to power and beauty’, 1925), directed by Nicholas Kaufmann and Wilhelm Prager. Western-style rancheras films were hugely popular in Mexico, with the most successful being Fernando de Fuentes’ Allá en El Rancho Grande (‘out on the great ranch’, 1936). Another Mexican genre from the period, cabaretera, involved innocent women venturing into sleazy nightclubs and being seduced into lives of wanton debauchery, with Alberto Gout’s Aventurera (‘adventuress’, 1949) being the acknowledged classic of this cult exploitation genre. Mexican exploitation became sexploitation in the 1970s with a cycle of sex comedies known as ficheras, named after Miguel M. Delgado’s Las ficheras (‘the burlesque girls’, 1975). Poetic RealismJean Vigo’s Zero de conduite (‘zero for conduct’, 1933) and L’Atalante — also released as Le Chaland qui passe (‘the passing barge’, 1934) — and Julien Duvivier’s Pépé le moko (1936; a polar, or police thriller), were the first films of France’s stylised, atmospheric Poetic Realism movement. Vigo completed only a handful of films before dying of tuberculosis. Poetic Realism’s most significant director was Marcel Carné, whose greatest films are Port of Shadows (Le quai des brumes, 1938), Le jour se lève (‘daybreak’, 1939), and Children of Paradise (Les enfants du paradis, 1945). The dream-like theatricality of this latter film would be equalled the following year in Jean Cocteau’s fantasy Beauty and the Beast (La belle et la bête). Jean Gabin, the star of Pépé le moko (‘Pépé the Toulonese’), Port of Shadows, and Jean Renoir’s La bête humaine (‘the human beast’, 1938), became the movement’s greatest icon, and appeared with Eric von Stroheim in Jean Renoir’s masterpiece La grande illusion (‘the great illusion’, 1937). Renoir’s deep-focus photography, constantly moving camera, long takes, and tragi-comic narratives were all used to greatest effect in The Rules of the Game (La règle du jeu) (1939), and the film is still acclaimed as European cinema’s greatest achievement. European cinema’s most questionable achievement is perhaps Leni Riefenstahl’s Nazi documentary Triumph of the Will (Triumph des Willens, 1934): an outstanding technical accomplishment, though also a lionisation of Adolf Hitler. Hollywood’s Golden AgeIn the 1930s, the hardships of the Depression were temporarily replaced by the glamour of Technicolor. Gone with the Wind (produced by David O. Selznick for his own studio) and The Wizard of Oz (from MGM), both directed by Victor Fleming in 1939, are the greatest Hollywood films of this period. Gone with the Wind is a sumptuous, epic romance, resplendent in three-strip Technicolor, after the hand-colouring of the 1900s, the tinting of the 1910s, and the two-strip Technicolor of the 1920s. The Wizard of Oz is particularly memorable for the moment when its sepia-tinted prologue in Kansas is transformed into the Technicolor paradise of the land of Oz. The first feature-length Technicolor production was The Gulf Between (Wray Bartlett Physioc, 1917), though this is now a lost film. The Hollywood studio system, at the height of its artistic and commercial success in the 1930s, began more than ever to produce films formulated according to specific genres. For example, in the 1930s, hundreds of westerns (known as ‘oaters’ and ‘horse operas’) were made, the best of which was John Ford’s Stagecoach (1939), starring John Wayne. Ford would continue to make westerns with Wayne for the next thirty years, though he also made the classic western My Darling Clementine with Henry Fonda in 1946. Universal produced a series of horror films in the 1930s, notably the Expressionist Frankenstein (1931) and Bride of Frankenstein (1935), both by British director James Whale, though the most unusual was Edgar G. Ulmer’s bizarre The Black Cat (1934). Bride of Frankenstein, a subversive parody of the genre conventions that Whale had established only a few years earlier, was the most remarkable horror film of the period. (Least notable is Tod Browning’s Dracula: its success, in 1931, launched the Universal horror cycle, though the film itself is stilted and creaky.) Alongside horror, the gangster genre also established itself in the early 1930s. Mervyn Le Roy’s somewhat dated Little Caesar (1930) was the first of the cycle, though far more powerful is William Wellman’s The Public Enemy (1931), released shortly afterwards. Both films, made by Universal, were swiftly surpassed, however, by Howard Hawks’ Scarface (1932), produced by Howard Hughes. The popularity of horror and gangster pictures was a cause of concern for the Catholic Legion of Decency and the Motion-Picture Producers and Distributors Association. The president of the MPPDA, Will Hays, drew up a Production Code forbidding excessive cinematic sex and violence. The musicals 42nd Street (Lloyd Bacon), Gold Diggers of 1933 (Mervyn Le Roy), and Footlight Parade (Lloyd Bacon), all choreographed by Busby Berkeley for Warner Bros. in 1933, were popular with audiences eager for escapism. They also inspired Brazil’s chanchada musicals such as Carnaval no Fogo (‘carnival in fire’, 1949) by Watson Macedo. Berkeley later directed the Technicolor fantasia The Gang’s All Here (1943). The ‘screwball’ comedy sub-genre made a star of Cary Grant, who appeared in Leo McCarey’s The Awful Truth (1937) and Howard Hawks’ Bringing Up Baby (1938). Screwball comedies, initiated by Hawks’ Twentieth Century (1934) and Frank Capra’s It Happened One Night (also 1934), were characterised by their fast-paced dialogue and ‘battle of the sexes’ humour. Screwball films were essentially frenetic variants of romantic comedies (‘rom-coms’), while romantic films and melodramas were regarded, somewhat dismissively, as ‘chick flicks’, epitomised by Now Voyager (Irving Rapper, 1942).  1940sFilms of the decade: The most important film of the decade was unquestionably Citizen Kane, directed by Orson Welles in 1941. With its deep-focus photography, stylised lighting, and overlapping dialogue, amongst other innovations, Kane is perhaps America’s most significant contribtion to the development of the cinema. For fifty years, it was voted the greatest film of all time in Sight and Sound magazine’s critics’ poll, though it was eventually replaced by Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) and Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975). Previous to Kane, Welles had directed and starred in The War of the Worlds, often cited as the world’s greatest radio production. Although he was given total artistic control over Citizen Kane, his later films (including The Magnificent Ambersons from 1942 and The Lady from Shanghai from 1947) were often revised by studios without his supervision. During World War II, producer Walt Disney’s animated features, including Pinocchio (Ben Sharpsteen, 1940), Dumbo (Ben Sharpsteen, 1941), and Bambi (David Hand, 1942), provided much-needed escapism, as Technicolor had done during the Depression in the 1930s. They consolidated Disney’s position at the forefront of animation, following the success of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (David Hand, 1937). Contrary to popular myth, Snow White was not the first feature-length animated film; that honour actually belongs to the Argentine film El Apostol (‘the apostle’) by Quirino Cristiani (1917). In Carol Reed’s British classic The Third Man (1949), the anticipation of Welles’ character Harry Lime rivals that of Kurtz in Apocalypse Now. Also in Britain, Ealing perfected their niche for comedy with Kind Hearts and Coronets (Robert Hamer, 1948) and The Ladykillers (Alexander Mackendrick, 1955), both starring Alec Guinness. Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger co-directed a series of British masterpieces in the 1940s, including the celestial fantasy A Matter of Life and Death (1946) — an influence on the 1987 Wim Wenders film Wings of Desire (Der Himmel Über Berlin) — produced by their company The Archers, launched in 1943. Powell and Pressburger’s films were far superior to the standard British productions of the period, cheap ‘quota quickies’ churned out following a 1927 law requiring a proportion of all exhibited films to be dosmestically produced. Film NoirAfter World War II, directors turned increasingly towards social realism and reverted to monochrome cinematography. This visually, thematically, and psychologically dark style was known as film noir, influenced by German Expressionism and the B-movie Stranger on the Third Floor (Boris Ingster, 1940). The term was originally used — somewhat derogatively — by French critics to describe the bleak Poetic Realist films of the late 1930s, but it was first applied to American detective films by Nino Frank in his article Un nouveau genre “policier”: l’aventure criminelle (‘a new type of detective film: criminal adventures’), published in the magazine L’Ecran français (no. 61) on 28th August 1946: “these “noir” films no longer have any common ground with run-of-the-mill police dramas.” (Frank’s essay was translated by Alain Silver in 1999; an earlier translation, by Connor Hartnett in 1995, mistranslated this sentence.) Recurrent motifs of film noir (and its melodramatic offshoot, film gris) include world-weary detectives, sultry femmes fatales, and urban crime narratives. Classic noirs include Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity (1944), Jacques Tourneur’s Out of the Past (1947; retitled Build My Gallows High for its UK release), and John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle (1950). Charles Laughton’s lyrical The Night of the Hunter (1955) is also stylistically a noir film. Cinematographer John Alton was responsible for some of the most visually stylish noirs, including The Big Combo (Joseph H. Lewis, 1955). Humphrey Bogart played the archetypal noir detectives Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon (John Huston, 1941) and Philip Marlowe in The Big Sleep (Howard Hawks, 1946). Marlowe was also played by Robert Montgomery, in Lady in the Lake (1947, directed by Montgomery); the film was shot entirely from a Marlowe’s perspective, thus Montgomery is only seen by the audience when he is reflected by a mirror. Bogart was perhaps the biggest star of the 1940s, and appeared in Michael Curtiz’s perfect wartime romance Casablanca (1942) in addition to his film noir roles. Other major stars of the time were James Stewart in Frank Capra’s It’s A Wonderful Life (1946) and Cary Grant in Howard Hawks’ brilliant screwball comedy His Girl Friday (1940). Noir themes such as urban crime were given more naturalistic treatments in a number of films both set in and filmed on the city streets. The first of these documentary-style ‘police procedural’ thrillers was The House on 92nd Street (1945) by Henry Hathaway, though the most well-known is Jules Dassin’s The Naked City (1948). Dassin later directed the gangster classic Rififi (Du rififi chez les hommes, 1955). Elia Kazan directed one of the best documentary-style thrillers, Panic in the Streets (1950). In a 1978 Journal of Popular Film article, The ‘Film Blanc’: Suggestions for a Variety of Fantasy, 1940–45, Peter Valenti proposed “film blanc” — describing feel-good fantasy films about guardian angels — as an optimistic alternative to film noir. He described A Matter of Life and Death as the apotheosis of film blanc, though he cited Beyond Tomorrow (A. Edward Sutherland, 1940) as the first example. The Hollywood musical, which Vincente Minnelli reinvented with Meet Me in St. Louis (1944) by integrating songs directly into the melodramatic narrative, was also the antithesis of film noir. Films noirs were named after a series of French crime novels, and a cycle of German films derived its name from a similar source. Krimi films, including Harald Reinl’s Der Frosch mit der Maske (‘the frog with the mask’, 1959) were named after a series of German crime novels. NeorealismThroughout the Fascist regime in Italy, one method of avoiding political censorship was simply to concentrate on producing escapist, apolitical cinema. These opulent, lightweight films, such as Mario Camerini’s Gli uomini, che mascalzoni... (‘men, what scoundrels’, 1932) starring future director Vittorio de Sica), were known as telefoni bianchi as they invariably included white Bakelite telephones as props. Another Italian cinema trend, calligrafismo (calligraphism), was characterised by the theatricality and prestige of literary adaptations such as Piccolo mondo antico (‘old-fashioned world’) by Mario Soldati (1941). But after Italy’s defeat in World War II, and the resultant lack of funds for its national film industry, the opulent escapism of the past was impossible. Instead, Luchino Visconti’s Obsession (Ossessione, 1943) took Italian cinema in a new direction: Neorealism. Obsession was filmed on location, bypassing the need for expensive studio sets, though its international distribution was restricted for copyright reasons. Neorealism came to international attention with the release of Roberto Rossellini’s Rome, Open City (Roma cittá aperta) in 1945. Open City achieved a sense of documentary realism through its use of non-professional actors and donated film-stock. Equally significant are the films of Vittorio de Sica, especially Shoeshine (Sciusciá, 1946) and Ladri di biciclette (1948; released as Bicycle Thieves in the UK and, less accurately, as The Bicycle Thief in the US). In the early 1950s, the Italian government funded film production only selectively, denying funds to overtly political films. Thus, elements of escapist comedy were introduced into Neorealist films, to make them more politically acceptable. This new style was known as Neorealism rosa (pink), and is typified by films such as Renato Castellani’s Due soldi di speranza (‘two cents worth of hope’, 1952). The comic element eventually eclipsed the Neorealist components altogether, and a distinctive Italian comedy style, commedia all’italiana, was born with the films of Mario Monicelli, notably I soliti ignoti (1958; released as The Big Deal on Madonna Street in the US, and Persons Unknown in the UK).  1950sFilms of the decade: The science-fiction genre gained popularity in the 1950s, and the best SF films of the decade are The Thing from Another World (Christian Nyby, 1951; produced by Howard Hawks), The Incredible Shrinking Man (Jack Arnold, 1956), and Invasion of the Body Snatchers (Don Siegel, 1956). The cycle was initiated by producer George Pal’s Destination Moon (Irving Pichel, 1950), though the low-budget ‘mockbuster’ Rocketship X-M (Kurt Neumann, 1950) was released before Pal’s film. Godzilla (ゴジラ, 1954), directed by Ishiro Honda, spawned the kaiju-eiga genre of Japanese monster films; it was released in America as King of the Monsters! with additional footage directed by Terry Morse. The most lamentable science-fiction films of the period were directed by Ed Wood, often cited as the world’s worst director. Wood’s films, including the notorious camp classic Plan Nine from Outer Space (1956), were certainly incompetent, though they were never dull. MGM made a series of Technicolor musicals produced by Arthur Freed in the 1940s and 1950s, including Meet Me in St Louis, and, most famously, Singin’ in the Rain (Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen, 1952). Often acclaimed as the greatest musical film ever made, Singin’ in the Rain was inspired by Hollywood’s transition to sound in the 1920s. The other key Hollywood-on-Hollywood film of the era was Sunset Boulevard (Billy Wilder, 1950), which starred two figures from the silent era: actress Gloria Swanson and director Erich von Stroheim. Alfred Hitchcock relocated from London to Hollywood in the 1940s (his greatest British films being the Expressionist The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog from 1926 and the espionage thriller The 39 Steps from 1935), and directed several films (including Notorious in 1946) under contract to David O. Selznick. Hitchcock directed his most acclaimed films during the 1950s, after extricating himself from the Selznick contract: Rear Window (1956) and Vertigo. Hitchcock’s greatest film, the shocking Psycho, was released in 1960, and influenced ‘slasher’ films such as Bob Clark’s Black Christmas (1974), John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978), and Wes Craven’s self-referential Scream (1996). The greatest star of the decade was undoubtedly Marilyn Monroe, perhaps the ultimate Hollywood sex symbol. Her renditions of Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (Howard Hawks, 1953) and I Wanna Be Loved by You in Some Like It Hot (Billy Wilder, 1959) are her career highlights. Monroe died in 1962, following an (accidental or suicidal) overdose of sleeping pills. In A Streetcar Named Desire (Elia Kazan, 1951), Marlon Brando introduced a new performance style to the cinema: ‘method acting’. Trained at the Actors’ Studio, he brought an unprecedented intensity to screen acting, notably in On the Waterfront (Elia Kazan, 1954). Director Kazan named names to senator Joe McCarthy during the Communist witch-hunts, and On the Waterfront, in which Brando’s character testifies against organised criminals, can be seen as Kazan’s self-justification for his actions. The new realism of Brando and James Dean’s acting style was complemented by a new generation of directors who produced their own films and thus bypassed the studio system. Shadows (1959), by John Cassavetes, was made completely independently in 16mm. Stanley Kubrick also produced his own films, directing independently since the early 1950s (his breakthrough being Paths Of Glory, 1957). In the 1960s, he relocated to England, where he directed the satirical masterpiece Dr. Strangelove, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), the stunning science-fiction epic 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and the stylised A Clockwork Orange (1971). (Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life, from 2011, was one of the few films to equal 2001’s epic scope.) The most determined of the independent producer-directors was Otto Preminger, who released The Moon Is Blue (1953) without Production Code approval. He also directed one of the best documentary-style noir thrillers, Where the Sidewalk Ends. Hollywood genre cycles of the 1930s, notably the gangster film and the western, were revisited in the 1950s. James Cagney starred in White Heat (Raoul Walsh, 1949), equalling and perhaps even exceeding the achievements of his original 1930s classic The Public Enemy. The western underwent considerable revision, influenced by the surprisingly radical High Noon (Fred Zinnemann, 1952). John Wayne, who starred in Howard Hawks’ Red River (1948), gave arguably his greatest performance in John Ford’s The Searchers (1956), introducing a new psychological complexity to the genre and presenting the traditional western hero as an anachronistic outcast. The dark and amoral world of film noir reached its logical conclusion with the apocalyptic Kiss Me Deadly (Robert Aldrich, 1955). Orson Welles, director of Citizen Kane, began his noir masterpiece Touch of Evil (1958) with a sequence that rivals Battleship Potemkin’s Odessa Steps and Psycho’s shower scene as the greatest sequence ever filmed. Its opening is a stunning and seemingly never-ending tracking shot. In Italy, Federico Fellini directed La strada (‘the road’, 1954), which was compared to French Poetic Realism, in contrast to Italy’s prevalent Neorealism movement. Italian cinema was gradually moving away from the social worthiness of Neorealism, and populist genres such as ‘spaghetti western’, giallo, peplum, and ‘eurospy’ would all flourish in the 1960s. Peplum films, featuring heroic protagonists and classical/mythological settings, began with Hercules (Le fatiche di Ercole, 1958) by Pietro Francisci, 1958. Eurospy films such as Sergio Grieco’s Agent 077: Mission Bloody Mary (Agente 077 missione Bloody Mary, 1965), Italian imitations of the James Bond series, were popular from circa 1964 until the end of the 1960s. In protest at the lack of social realism in British films, a Free Cinema group was established, releasing a series of short statements between 1956 and 1959, concluding with: “FREE CINEMA is dead! Long live FREE CINEMA!” The group initially produced short documentaries that focused on working-class culture and recreation, including O Dreamland (Lyndsay Anderson, 1953). The Free Cinema directors then progressed from documentaries to feature-films: ‘kitchen sink’ dramas about northern ‘angry young men’, such as Room at the Top (Jack Clayton, 1959) and Look Back in Anger (Tony Richardson, 1959), true to the social realist origins of the movement.  Hollywood v. TelevisionThe increasing popularity of television forced Hollywood to introduce numerous technological innovations, such as widescreen and 3D, in order to compete for audiences. The first widescreen process of the 1950s, the triptych Cinerama format used for This Is Cinerama (Merian C. Cooper, 1952), was directly inspired by the Polyvision system used in the 1920s, though it added a curved screen to provide a sense of immersive depth. 20th Century Fox’s CinemaScope anamorphic widescreen format (The Robe; Henry Koster, 1953), based on Henri Chretien’s Hypergonar system, soon replaced the more cumbersome Cinerama. The triptych concept was revived in 2013, for the South Korean ScreenX system, showcased by Kim Jee-Woon’s short film The X. In order to fully demonstrate the panoramic potential of the new widescreen formats, a number of biblical epics of the 1920s were remade in widescreen Technicolor splendour, including Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (William Wyler, 1959). The popularity of widescreen led to more spectacular formats, such as the 70mm IMAX system (Tiger Child; Donald Brittain, 1970). 3D was another gimmick used by Hollywood to lure audiences away from television. It had been used previously in the silent film The Power of Love (Nat G. Deverich and Harry K. Fairall, 1922), though it was promoted as a mainstream attraction in the 1950s. The success of Bwana Devil (Arch Oboler, 1952), filmed in Natural Vision 3D, led to science-fiction films such as Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) and It Came from Outer Space (1953), both by Jack Arnold, also receiving 3D releases. Some of the more esoteric 1950s gimmicks included Psycho-Rama, a process by which images and text appeared subliminally in the horror film My World Dies Screaming (Harold Daniels, 1958). There were also two olfactory gimmicks: Smell-O-Vision, for Scent Of Mystery (Jack Cardiff, 1960); and Aroma-Rama, for Behind the Great Wall (La muraglia cinese; Carlo Lizzani, 1959). (A later gimmick utilised scratch ’n’ sniff cards: Odorama in 1981 for John Waters’ Polyester.) Director William Castle (The Tingler, 1959) was the undisputed king of gimmicks in the 1950s, though his inventive marketing schemes were more memorable than the films they promoted. To provide a unique alternative to television, American drive-in cinemas began screening sensationalist, melodramatic exploitation films. These ranged from disposable WIP (women in prison) films such as Caged (John Cromwell, 1949) to more substantial JD (juvenile delinquent) films such as The Wild One and Rebel Without a Cause. Though many 1950s exploitation films were low-budget, absurdly moralistic, and instantly out-of-date, there are two notable exceptions: the ‘teensploitation’ films The Wild One starring Marlon Brando and Rebel Without a Cause starring James Dean. Brando was one of a number of young male actors who starred in juvenile delinquent films about youth rebellion, the prototypical example being Brando’s own performance in The Wild One (Laslo Benedek, 1953). James Dean starred in the yet more iconic Rebel Without a Cause (Nicholas Ray, 1955), released after Dean had been killed in a car accident. A parallel trend existed in Japanese cinema, with a genre known as taiyozoku inaugurated by Takumi Furukawa’s Season of the Sun (太陽の季節, 1956). World CinemaDuring the 1950s, directors such as Satyajit Ray, Federico Fellini, Akira Kurosawa, and Ingmar Bergman all established international reputations for the cinema industries of their respective countries. In Sweden, Wild Strawberries (Smultronstället, 1957), the masterful religious allegory The Seventh Seal (Det sjunde inseglet, 1957), and, later, Persona (1966), marked director Ingmar Bergman as one of world cinema’s greatest artists. Japan’s master director Akira Kurosawa achieved international acclaim for his jidai-geki films Rashomon (羅生門, 1950) — with its innovative use of contradictory flashbacks — and the epic Seven Samurai (七人の侍, 1954), both starring Toshiro Mifune. Kurosawa’s gendai-geki films, which critiqued post-War Japanese society, include the noir-influenced Stray Dog (野良犬, 1949), the profoundly humanist 生きる (‘to live’, 1952), and the suspense thriller High and Low (天国と地獄, 1963). Japan’s other greatest filmmakers, Kenji Mizoguchi and Yasujiro Ozu, had, unlike Kurosawa, been directing ever since the silent era, though their greatest films were also made in the 1950s. Mizoguchi’s work — Ugetsu (雨月物語, 1953) and Sansho the Bailiff (山椒大夫, 1954) — has been compared to that of French director Jean Renoir, as he shares Renoir’s use of deep-focus photography, constantly moving camera, and tragi-comic narrative. By contrast, Ozu’s Tokyo Story (東京物語, 1953) contains virtually no camera movement at all. Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu is one of Japan’s most acclaimed kaidan-eiga, films featuring ghost stories, an early example of which is Mizoguchi’s own Passion of a Woman Teacher (狂恋の女師匠, 1926). The dramatic realism of Ugetsu is atypical of the genre, though, as most examples are supernatural horror stories. Nobuo Nakagawa, the greatest of all Japanese horror directors, made an obaneneko-mono film about a ghostly cat, The Mansion of the Ghost Cat (亡霊怪猫屋敷, 1958). In the 1930s, a series of Japanese literary adaptions (bungei-eiga) was produced, including 恋の花咲く 伊豆の踊子 (‘the dancing girl of Izu’, 1933) by Heinosuke Gosho and 若い人 (‘youth’, 1937) by Shiro Toyoda. In the 1940s, there were jingoistic war dramas (kokusaku-eiga) such as ハワイ・マレー沖海戦 (‘war at sea from Hawaii to Malaya’, 1942) by Kajiro Yamamoto, which gave a Japanese perspective on the Pearl Harbor attack. However, the 1950s remains unmatched as a golden age for Japanese cinema. The short-lived keiko-eiga films of the 1920s inspired a new genre of social-realist Japanese cinema, known as shakai-mono. The director who dominated this genre was Tadashi Imai, well known for the unsentimental nature of his films (called nakanai) such as ひめゆりの塔 (‘Tower of Himeyuri’, 1953). By contrast, other Japanese films tended to be highly melodramatic (namida chodai), typified by Kinoyu Tanaka’s Eternal Breasts (乳房よ永遠なれ, 1955). Another 1920s Japanese genre, shomin-geki, was also revived in the 1950s, branching into several new sub-genres. Mikio Naruse’s Repast (めし, 1951), for instance, was an example of the tsuma-mono sub-genre (films about wives). Keisuke Kinoshita’s Tragedy of Japan (日本の悲劇, 1953) represents the haha-mono sub-genre (films about mothers). The most popular of these new shomin-geki films was Heinosuke Gosho’s 煙突の見える場所 (‘where chimneys are seen’, 1953). In India, Satyajit Ray directed Pather Panchali (পথের পাঁচালী) (‘song of the little road’, 1955), in stark contrast to the musical decadence of Bollywood cinema. Ray’s film marked a temporary shift away from populist Bollywood fantasies, helping to foster an Indian culture of non-populist films known broadly as ‘parallel cinema’, including art films (kalamatka) and experimental cinema (prayogika). In the 1960s, New Indian Cinema, led by Bhuvan Shome (Mrinal Sen, 1969), offered another alternative to Bollywood escapism. With Arun Kaul, Mrinal Sen wrote a Manifesto of the New Cinema Movement, criticising traditional Indian cinema, in 1968: “New Cinema Movement is conceived as a self-sufficient structure embracing all three branches of filmmaking: production, distribution and exhibition.” Shyam Benegal’s debut film The Seedling (Ankur, 1974) has been described as an example of ‘middle cinema’, as it represented a balance between parallel cinema and the populism of the mainstream Indian film industry.